In a world where artificial intelligence, exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, is reshaping our world, the human touch of design thinking becomes even more crucial. You might already be familiar with design thinking and curious about how to harness it alongside AI, or perhaps you’re new to this method. Regardless of your experience level, I’m going to share why design thinking is your human advantage in an AI-world. We’ll explore its impact on students and educators, particularly when integrated into the curriculum to design learning experiences that are both innovative and empathetic.

Back in 2017, I spearheaded a two-year research study at Design39 Campus in San Diego, CA, focusing on how educators used design thinking to transcend traditional educational practices. This study was pivotal in understanding how to scale from pockets of innovation to a culture of innovation. It’s rare to see a public school integrate these practices, and I always wondered, “Why is this the exception and not the norm?” How might design thinking when combined with AI tools, complement standards-based curricula by prompting students to tackle real-world challenges. We investigated the methods educators used to learn about design thinking and how they crafted learning experiences at the nexus of knowledge, skills, and mindsets, aiming to foster creative problem-solving in an increasingly AI-integrated world. The results revealed it had nothing to do with the technology. It had to do with people.

What is Design Thinking in Education?

Design thinking is both a method and a mindset.

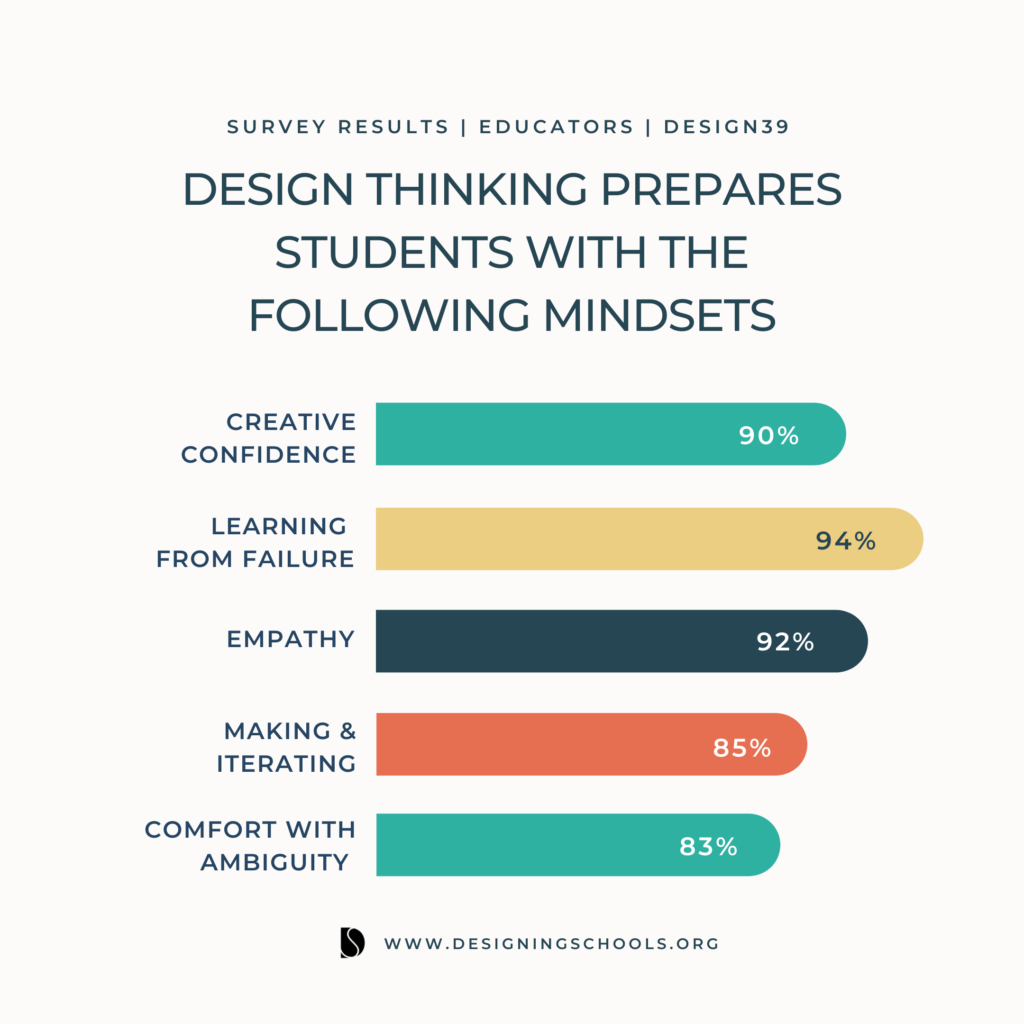

What makes design thinking unique in comparison to other frameworks such as project based learning, is that in addition to skills there is an emphasis on developing mindsets such as empathy, creative confidence, learning from failure and optimism.

Seeing their students and themselves enhance and develop their skills and mindset of a design thinker demonstrated the value in using design thinking and fueled their motivation to continue. In addition, it strengthened their self-efficacy and helped them embrace, not fear change.

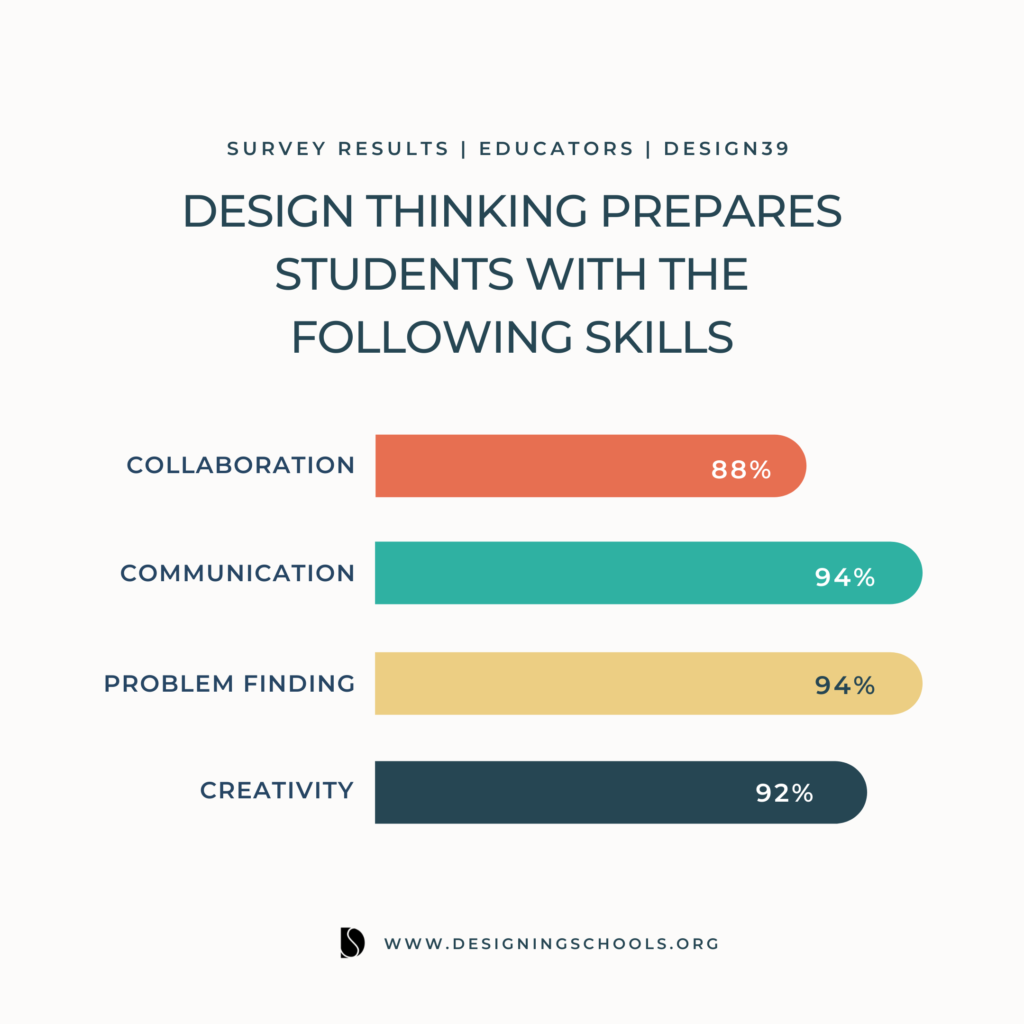

The results indicate strong agreement amongst the educators between developing in demand skills such as creativity, problem finding, collaboration and communication and practicing design thinking.

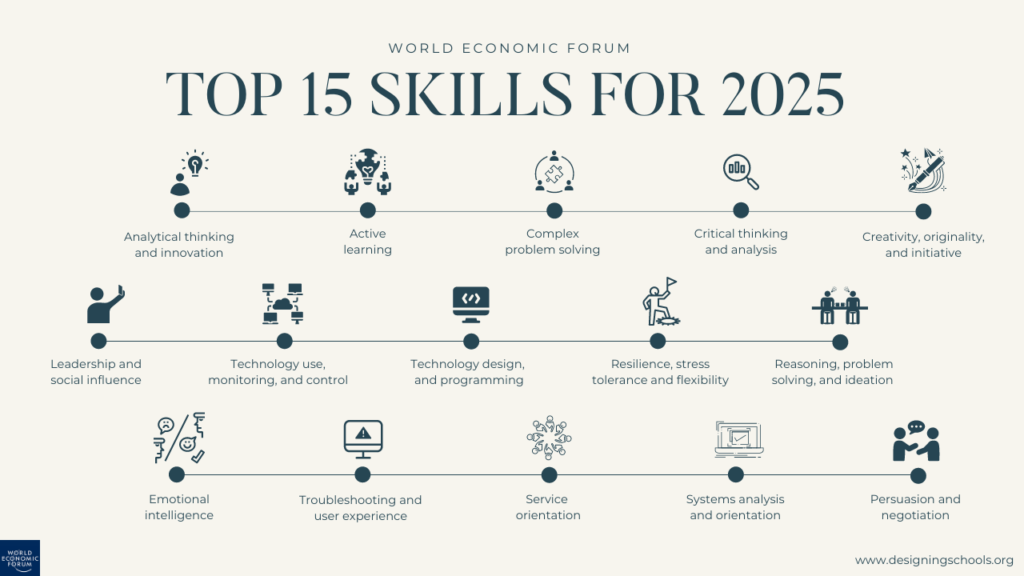

As workplaces determine how to leverage new and emerging technologies in ways that serve humanity, the two critical skills expected will be the ability to solve unstructured problems and to engage in complex communication, two areas that allow workers to augment what machines can do (Levy & Murnane, 2013.)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) call this era, “The Second Machine Age,” characterized by advances in technology, such as the rise of big data, mobility, artificial intelligence, robotics and the internet of things. The World Economic Forum calls this era, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

Regardless of the name we give this era, Schwab warned, as did Brynjolfsson and McAfee, that failure by organizations to prepare and adapt could cause inequality and fragment societies.

That era that we once talked about, is not here.

The rise of generative Ai.

As Erik Brynjolfsson shares, “There is no economic law that says as technology advances, so does equal opportunity.” The World Economic Forum reinforces this by sharing, that while the dynamics of today’s world have the potential to create enormous prosperity, the challenge to societies, particularly businesses, governments and education systems, will be to create access to opportunities that will allow everyone to share in the prosperity.

Schwab, Brynjolfsson and McAfee advocate for schools being able to play a powerful role in shaping a future that is technology-driven and human-centered. Design thinking, a human-centered framework is one method that can provide educators with the skills and mindset to navigate away from the traditional model established during the industrial area. To a learner-centered vision where we design learning experiences at the intersection of knowledge, skills, and mindsets.

The Future of Work

Designing schools for today’s learner is not just about solving a workforce or technology challenge. It’s also about solving a human challenge, where every individual has the access and opportunity to reach their potential.

Despite the changing expectations of the workplace brought forth by this era, today’s education systems largely remain unchanged. Leaving graduates without the knowledge, skills and mindsets to thrive in future workplaces and as citizens. Furthermore, the lack of equity has led to what Paul Attewell calls a growing digital use divide deepening the fragmentation of society.

A decade ago, some of the most in-demand occupations or specialties today did not exist across many industries and countries. Furthermore, 60% of children in kindergarten will live in a world where the possible opportunities do not yet exist (World Economic Forum, 2017).

In Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work, McKinsey states that 60% of all occupations have at least 30% of activities that can be automated. 40% of employers say lack of skills is the main reason for entry level job vacancies. And 60% of new graduates said they were not prepared for the world of work in a knowledge economy, noting gaps in technical and soft skills. Before our experience with ChatGPT I’m reminded of Imaginable by Jane McGonigal where she shares, “Almost everything important that’s ever happened, was unimaginable shortly before it happened.”

With an influx of technology over the past decade, with iPads and Chromebooks, and now the acceleration of AI technology, particularly over the past year, we have to wonder what gaps exist that prevent us from accelerating and scaling the change we want to see in schools.

One reason is that this challenge is complex and overwhelming. This is where design thinking practices are helpful in moving from idea to impact. Design thinking practices provide the structure and scaffolds needed to take a complex idea and simplify it.

The Design Thinking Process

Too often design thinking is seen as a series of hexagons to jump through. Check off one and move onto the next. Design thinking is a non-linear framework that nurtures your mindset toward navigating change.

It can be used in three areas:

- Problem finding

- Problem solving

- Opportunity exploration

The design thinking model is nonlinear. Resulting in a back and forth between the stages of inspiration, ideation and implementation, in an effort to continuously improve upon their potential solution (Shively et al., 2018). These stages were expanded by the d.School into empathy, define, ideate, prototype and iterate. In fact, there are many exercises that can be used to apply each area of the process.

Let’s walk through each phase. Then I’ll share examples of how it is being used. I also want to preface this by saying that simply going through these stages is where most people misunderstand design thinking and don’t see the results they hoped for. These phases are here to help you develop an action-oriented mindset. Moving from identifying a problem to designing and then testing a solution to quickly get feedback. Each of these phases have numerous exercises to also help facilitate experiences based on your scenario.

Phase 1: Empathy

When you begin with empathy, what you think is challenged by what you learn. This alone is what makes design thinking so unique and is the first phase. During the empathy stage, you observe, engage and immerse yourself in the experience of those you are designing for. Continuously asking, “why” to understand why things are the way they are.

This phase is where we see the most challenges, yet this phase is the most critical. An empathy map is probably the most common exercise. Yet there are others such as, “Heard, Seen, Respected.” Another challenge in this area is not speaking directly to the user. For example, I’ve sat in many “design thinking” experiences where the group will speculate on behalf of the users. For example, educators speculating about parents, administrators speculating about teachers.

The purpose behind an empathy exercise is that when we begin with empathy, what we think is challenged by what we learn. While you can practice with each other, ultimately you must speak directly to who you are designing for.

Phase 2: Define

During the define stage you unpack the empathy findings and create an actionable problem statement often starting with, “how might we…” This statement not only emphasizes an optimistic outlook, it invites the designer to think about how this can be a collaborative approach.

Phase 3: Ideate

During the ideate phase you generate a series of possibilities for design. The focus here is quantity not quality. As you want to generate as many possibilities to see how they may merge together. As Guy Kawasaki shares, “Don’t worry be crappy.” Feasibility is not important at this step. Rather the key is to not think about what is possible but what can be possible. At the end, one of the ideas, or the merging of many ideas, is chosen to expand upon in the next phase.

This is another phase where we see challenges. It is not enough to simply tell someone to get a piece of paper and then come up with lots of ideas. As adults, this is incredibly challenging and is also a muscle that needs to be developed. In fact, one of my favorite exercises is 1-2-4-all. Another is walking questions, where the prompt begins with “What if…” and then after each person writes something it is handed to the person on their right.

Phase 4: Prototype

During the prototype phase, ideas that were narrowed down from ideation are created in a tangible form so that they can be tested. During this phase, the designer has an opportunity to test their prototype and gain feedback.

Phase 5: Iteration

By quickly testing the prototype, the user can refine the idea. And have a deeper understanding to go back and ask questions to the group they are designing for. The feedback received from the user allows the designer to engage in a deeper level of empathy to refine the questions asked and the problem being defined. This brings us back to phase 1.

You can find more of these exercises to lead your group through each phase at sessionlab.com.

As schools strive to create student learning experiences that prepare them for their future, design thinking can play a critical role in complementing students’ knowledge with the skills and mindsets to be creative problem solvers.

Examples of Design Thinking in K12

While new approaches tend to be viewed with skepticism, an increasing number of studies are coming forward reflecting the promise of transferability of skills and mindsets from the classroom to real-world problems when utilizing design thinking. As expectations are raised about what student skills and mindsets are needed, the level of support for educators must increase as well to experience success in new strategies and the outcomes they promise.

When student learning experiences include design thinking, their skills continue to be enhanced and developed. This in turn allows them to apply these strategies to be problem finders and problem solvers. Helping them be more comfortable with change and empowering them to solve unstructured problems. And work with new information, gaining knowledge, skills and mindsets that cannot be found in the confines of a textbook.

In “The Second Machine Age,” the authors share:

Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education. Because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only “ordinary” skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate.

The Second Machine Age | Erik Brynjolfsson | Andrew McAffee

Design thinking strengthens the mindsets and skills that today’s world demands with the ability to become creative problem solvers. Through nurturing the skills and mindsets developed through engaging in design thinking, schools can create more equitable use environments for all learners that leverage technology to accelerate creative tasks that can bridge the digital use divide.

Case Study 1: Design Thinking in Grade 6

A recent study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education highlights that through instruction, students transfer design thinking strategies beyond the classroom. And that the biggest benefits were to low-achieving students (Chin et al., 2019).

The study included 200 students from grade 6. The researchers worked with the educators during class time to coach half the group of students on two specific design thinking strategies. And then assigned them a project where they could apply these skills.

The two strategies included seeking out constructive feedback and identifying multiple possible outcomes to a challenge. Each of these strategies were designed to prevent what the researchers called, “early closure”. Identifying the potential solution before examining the problem.

After class the students were presented with different challenges to see how they would approach them. The students who were taught about constructive criticism asked for feedback when presented with the new challenge and were more likely to go back and revise their work.

This area was significant, as a pre-test revealed that low-achieving students were behind their high achieving peers when seeking out feedback, a gap that the researchers say disappeared after classroom instruction, highlighting the need for this to be taught to all students, not just advanced students in electives.

As Attewell shares, “Placing computers in the hands of every student is not a solution because the challenge lies in addressing the “digital use divide – changing the tasks that students do when provided with computers.”

He further highlights the students who gain the types of skills highlighted by the Future of Jobs Report are white and affluent students. These students are more likely to use technology to develop trending skills with greater levels of adult support. Whereas minority students are more likely to use it for rote learning tasks, with lower levels of adult support.

While design thinking is often found in pockets, presented to students already interested in this area, or the students who are in certain electives, the study led by the Stanford Graduate School of Education demonstrates the advances that can be made when this is offered to all students.

Case Study 2: Design Thinking in Geography

Another study (Caroll et al., 2010) focused on the implementation of a design curriculum during a middle school geography class. And explored how students expressed their understanding of design thinking in classroom activities, how affective elements impacted design thinking in the classroom environment and how design thinking is connected to academic standards and content in the classroom. The students were a diverse group with 60% Latino, 30% African-American, 9% Pacific Islander and 1% White.

The task was for students to use the design process to learn about systems in geography. The study found that students increased their levels of creative confidence. And that design thinking fostered the ability to imagine without boundaries and constraints. A key element to success was that educators needed to see the value of design thinking. And it must be integrated into academic content.

A challenge often associated with design thinking in education is not integrating it into mainstream education as an equitable experience for all learners despite showing that lower achieving students benefit more (Chin et al, 2019).

If students are to experience dynamic learning experiences, then organizations must raise the level of support for educators and give them the time and space to learn and integrate design thinking.

How Educators Use Design Thinking

Educators are facing a number of challenges in their professional practice. Many of the requirements today are tools and methods they did not grow up with. Furthermore, the profession is tasked with designing new methods often within traditional systems that have constraints that may serve as roadblocks to change (Robinson & Aronica, 2016).

A 2018 study by PwC with the Business Higher Education Forum shared that an average of 10% of K-12 teachers feel confident incorporating higher-level technology that affords students the opportunity to use technology to design learning that is active, not passive.

As a result, students do not spend much time in school actively practicing the higher-level trending skills expected by employers. Moreover, the report shows that more than 60% of classroom technology use is passive, while only 32% is active use. While the study suggests that many teachers do not have the skills to engage students in the active use of technology, 79% said they would like to have more professional development for how to leverage technology to design learning that is active.

Case Study 3: Design39 Campus

As I shared earlier I led a two-year research study at Design39 Campus. The study examines how it helped teachers evolve their practice. At Design39 teachers are called “Learning Experience Designers” (LEDs). Borko and Putnam (1995) share that how educators think is related to their knowledge. To understand how LEDs are using design thinking to complement the standards-based curriculum, it was important to understand how they acquired and applied this knowledge.

Despite design thinking having its roots outside of education, when asked, “What does design thinking mean to you?” The LEDs identified many commonalities amongst their own work as educators and design thinking. Moreover, they appreciated the alignment of their work with the vocabulary and structure of the design thinking framework.

Over 50% of the LEDs interviewed identified design thinking as providing them with a common vocabulary and structure for what they already do. The LEDs identified educators as inherent design thinkers due to the shared human-centered focus of working with users. In this experience educators design challenges with cyclical learning tasks involving testing, feedback and iteration, and a design mindset to address the wide variety of complex problems within their individual classrooms and across education organizations.

One LED shared:

I just look at it as a process, a process in my mind that we kind of naturally go through as educators, and so with the design thinking process I feel that it is codifying what we do and so we start off always in empathy and empathy is the heart of design thinking and so we are problem solving, who are we problem solving for – people, our learners and so this entire process that we go through of brain dumping it, trying it, getting feedback and coming back to it again so that we can make sure we were really insightful about what the problem really was for the users and we continue around this process to fine tune a potential solution is the design thinking process.

Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

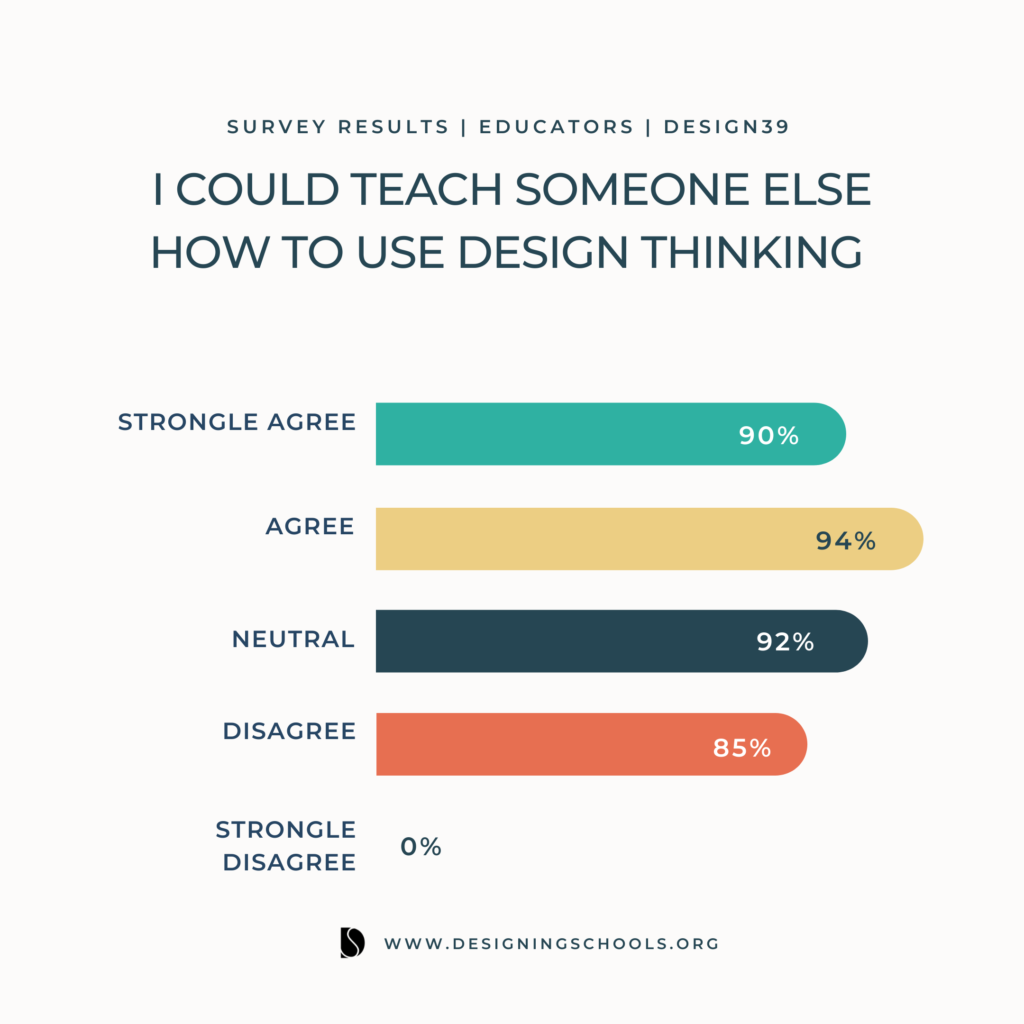

One of the ways mastery of knowledge is demonstrated is by teaching others. To assess their mastery of design thinking in education, learning experience designers were asked to describe their confidence in teaching someone else how to integrate design thinking into their curriculum.

Many LEDs acknowledged that although this is what it often looked like in the first year of the school opening, they have since had the time, space and collaborative opportunities to explore and create deeper integration. This was a point of reference mentioned by 78% of LEDs.

One LED shared:

I think a lot of people see design thinking as one science activity, we design think everything from rules to problems that come up in the playground, it’s all through the day, they (the learners) are always looking for problems to solve.

Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

In another example, four LEDs made a note using the exact same language that “design thinking is not always cardboard and duct tape.” What allows them to design learning that is more meaningful one LED highlighted:

Not every day is about using duct tape and cardboard, sometimes to do the design to solve the problems you have to hunker down and read and research and so some days, design thinking is highlighting and taking notes.

Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

Another LED elaborated on this idea by sharing that

Design thinking is a way of thinking, not always a product that is created at the end.

Learning Experience Designer | Design39 Campus

LEDs in all focus groups shared how ultimately design thinking was an opportunity to design lessons that are “bigger than we are.”

This allowed for the LEDs to design learning experiences. With this, the end result was not to just design a potential solution to a challenge that was identified. Or to simply go from one standard to another, checking off boxes along the way, but that the solution, the work the learners were doing lived beyond the classroom for an authentic audience, where learners are working on real world problems and presenting their solutions to a real world audience.

Almost all of the LEDs shared that to them design thinking was a mindset. It is a process of inquiry that allowed for a more human centered environment where the learner was the focus.

This highlighted a critical shift in the culture at Design39, an element Sarason (2004) discussed in saying no one ever asks:

“Why is school not a place where educators learn as well?”

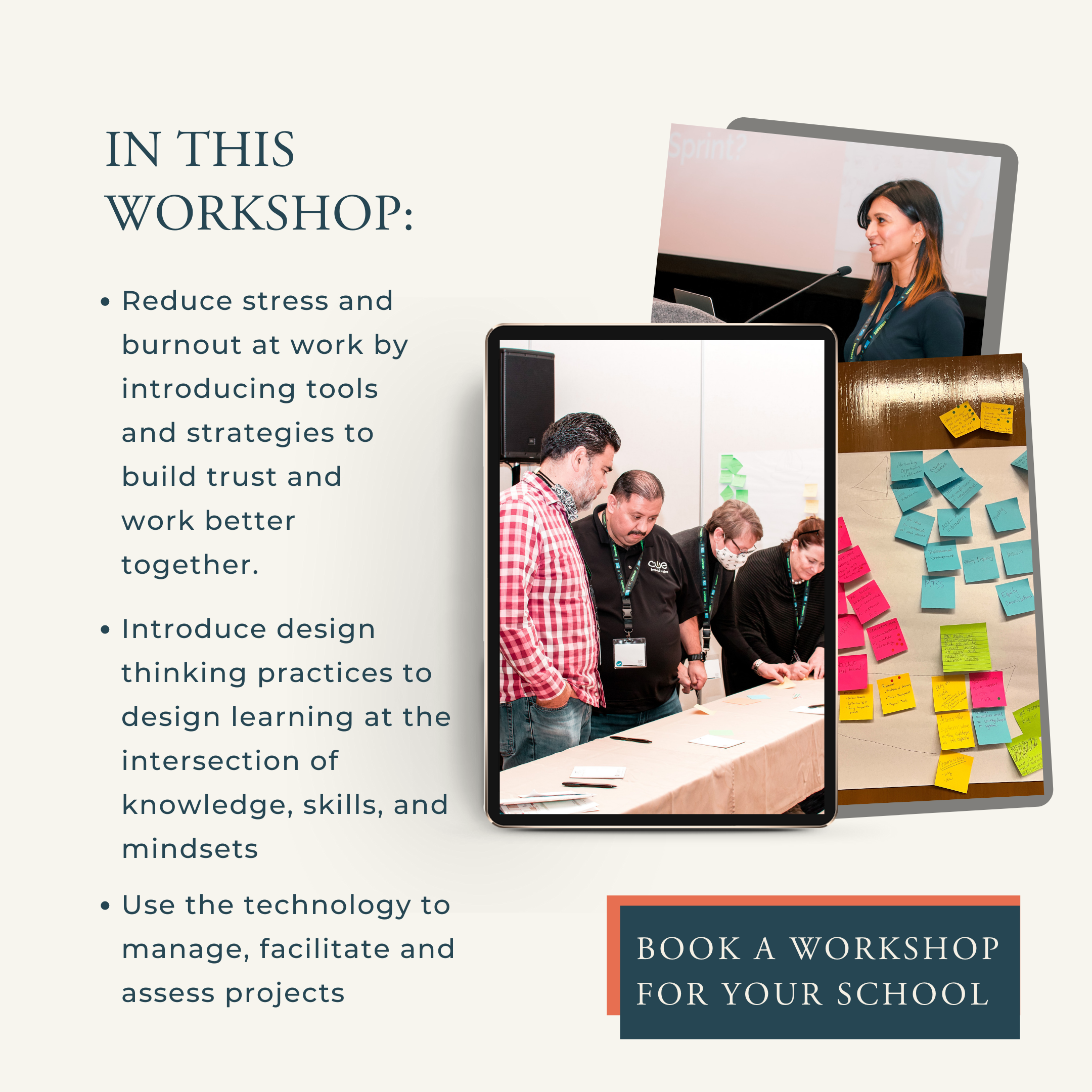

Bring a Design Thinking Workshop to Your School

We’ve invested in technology. Now it’s time to invest in people. Let’s discuss how design thinking practices can enhance the work you are doing in your school, giving everyone the mindset and skills to navigate change with enthusiasm and optimism. Use this calendar to schedule a time with Sabba to discuss bringing a workshop to your school. Workshops can be delivered both virtually and in-person.

Citations

Attewell, P. (2001). The first and second digital divides. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 252-259

Borko, H., & Putnam, R.T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. Gusky & M. Huberman (Eds), Professional development in education: New paradigms and practices (pp.35-65). Teachers College Press.

Brown, T & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Science Review, 8(1), 30-35.

Brynjolfsson, E. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies (1stt ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Carroll, M., Goldman, S., Britos, L., Koh, J., Royalty, A., & Hornstein, M. (2010). Destination, imagination and the fires within: Design thinking in a middle school classroom. International Journal of Art and Design Education, (29)1, 37-53.

Chin, D. B., Doris, Blair, K.P., Wolf, R., & Conlin, L., Cutumisu, M., Pfaffman, J., Schwartz, D.L. (2019). Educating and measuring choice: A test of the transfer of design thinking in problem solving and learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 1-44.

Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2013). Dancing with Robots. NEXT Report.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017). Technology, Jobs and the Future of Work. McKinsey.

PwC (2017). Technology in U.S. Schools: Are we preparing our students for the jobs of tomorrow. Pricewater House Coopers. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/about-us/corporate-responsibility/library/preparing-students-for-technology-jobs.html.

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2016). Creative schools: the grassroots revolution that’s transforming education. Penguin Books.

Shively, K., Stith, K.M., & Rubenstein, L.D. (2018). Measuring what matters: Assessing creativity, critical thinking, and the design process. Gifted Child Today, 41(3) 149-158.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum.

I’m Sabba.

I believe that the future should be designed. Not left to chance.

Over the past decade, using design thinking practices I've helped schools and businesses create a culture of innovation where everyone is empowered to move from idea to impact, to address complex challenges and discover opportunities.

stay connected

designing schools

[…] importance of learning experiences at the intersection of developing learning skills and mindsets. Design thinking is one approach that can help you master both. In my experience it’s rare that design thinking […]